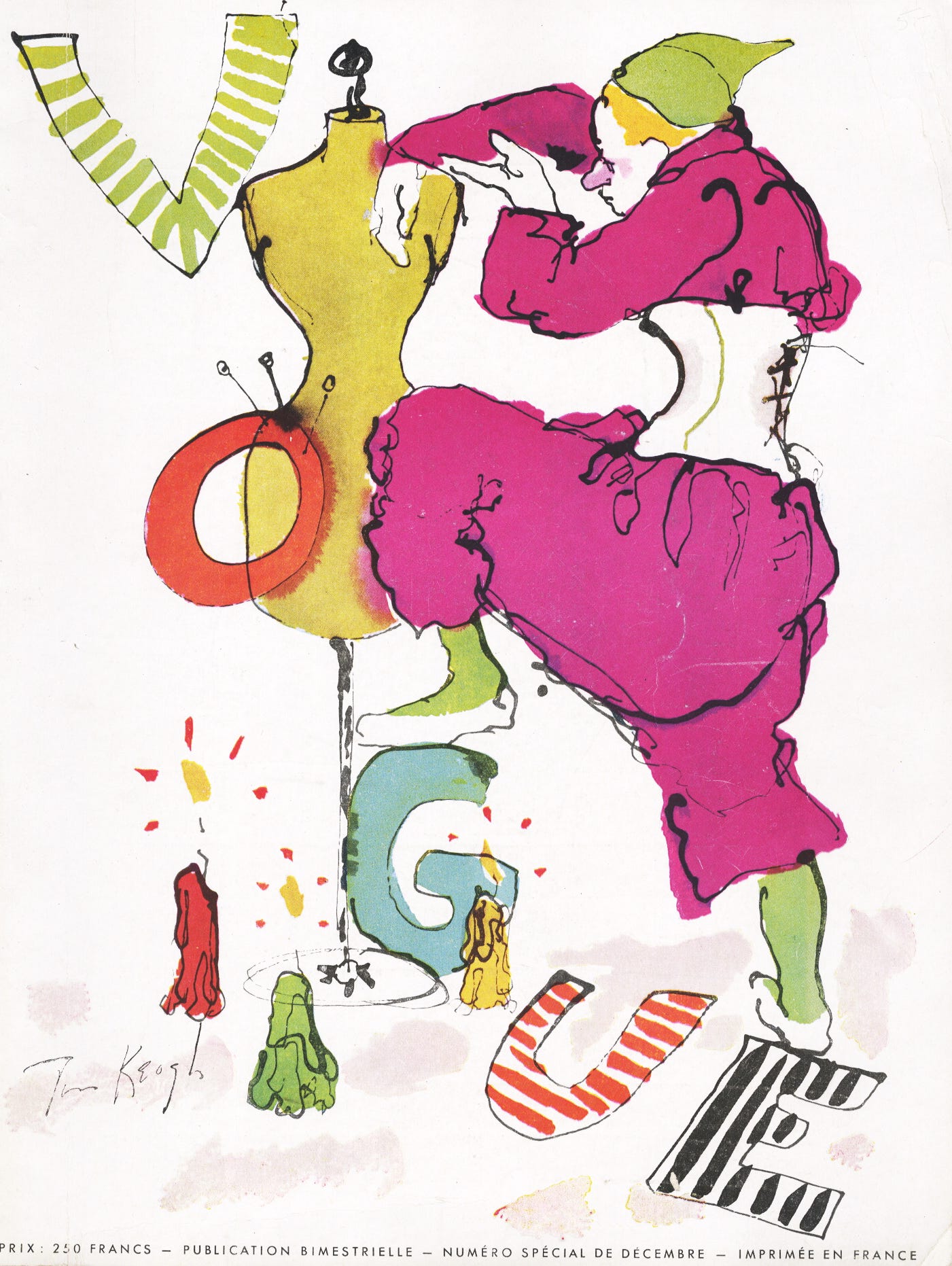

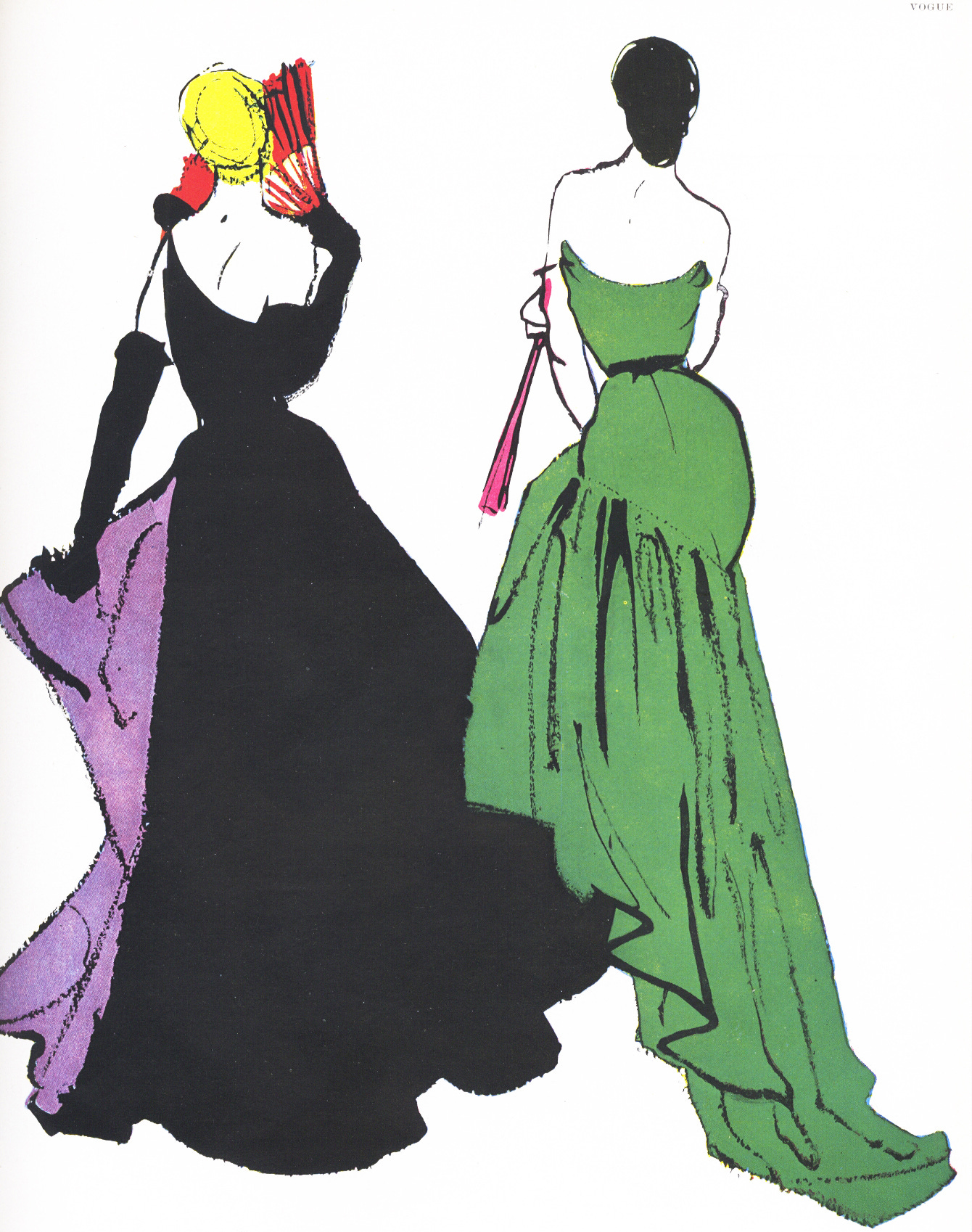

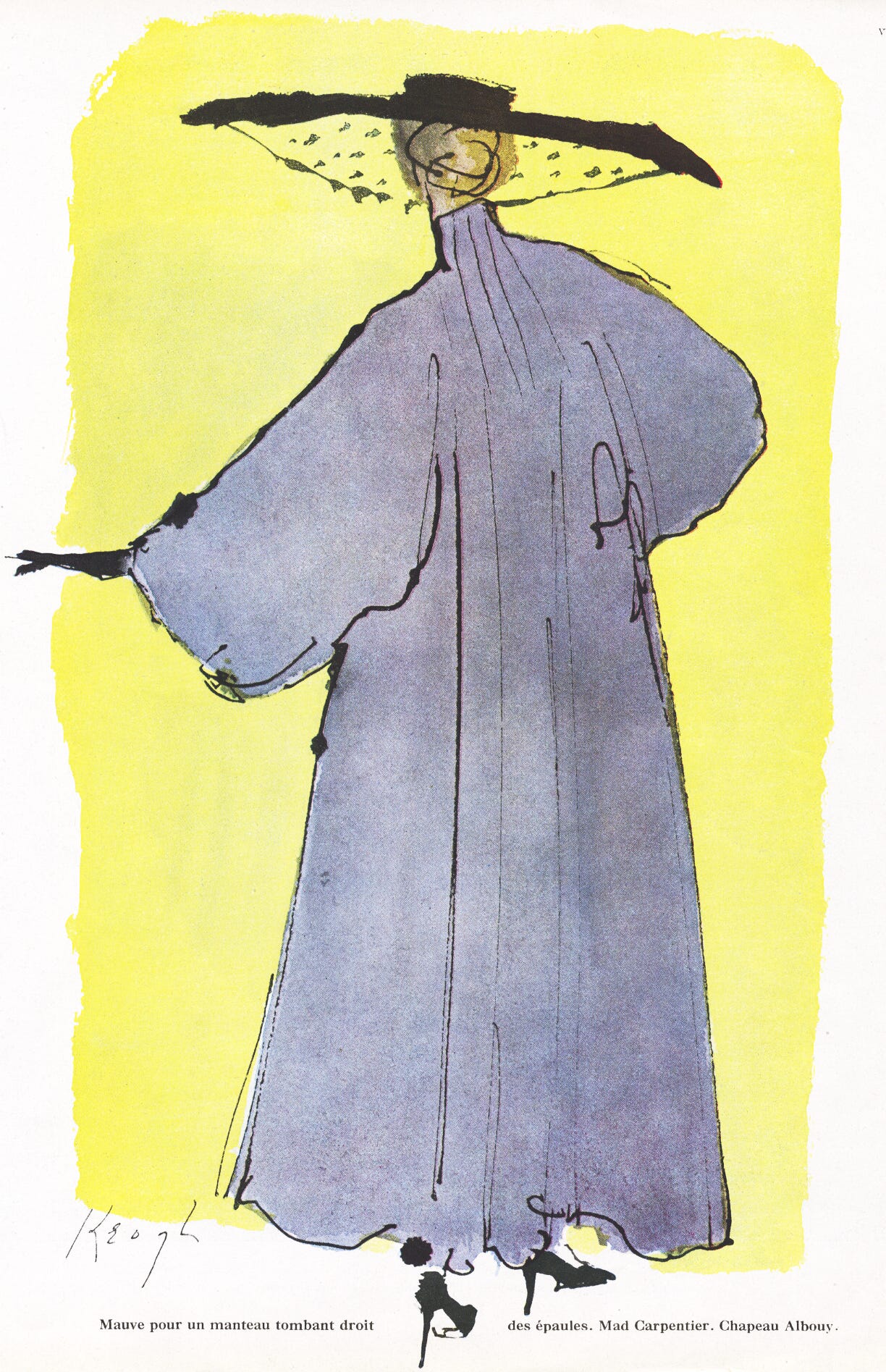

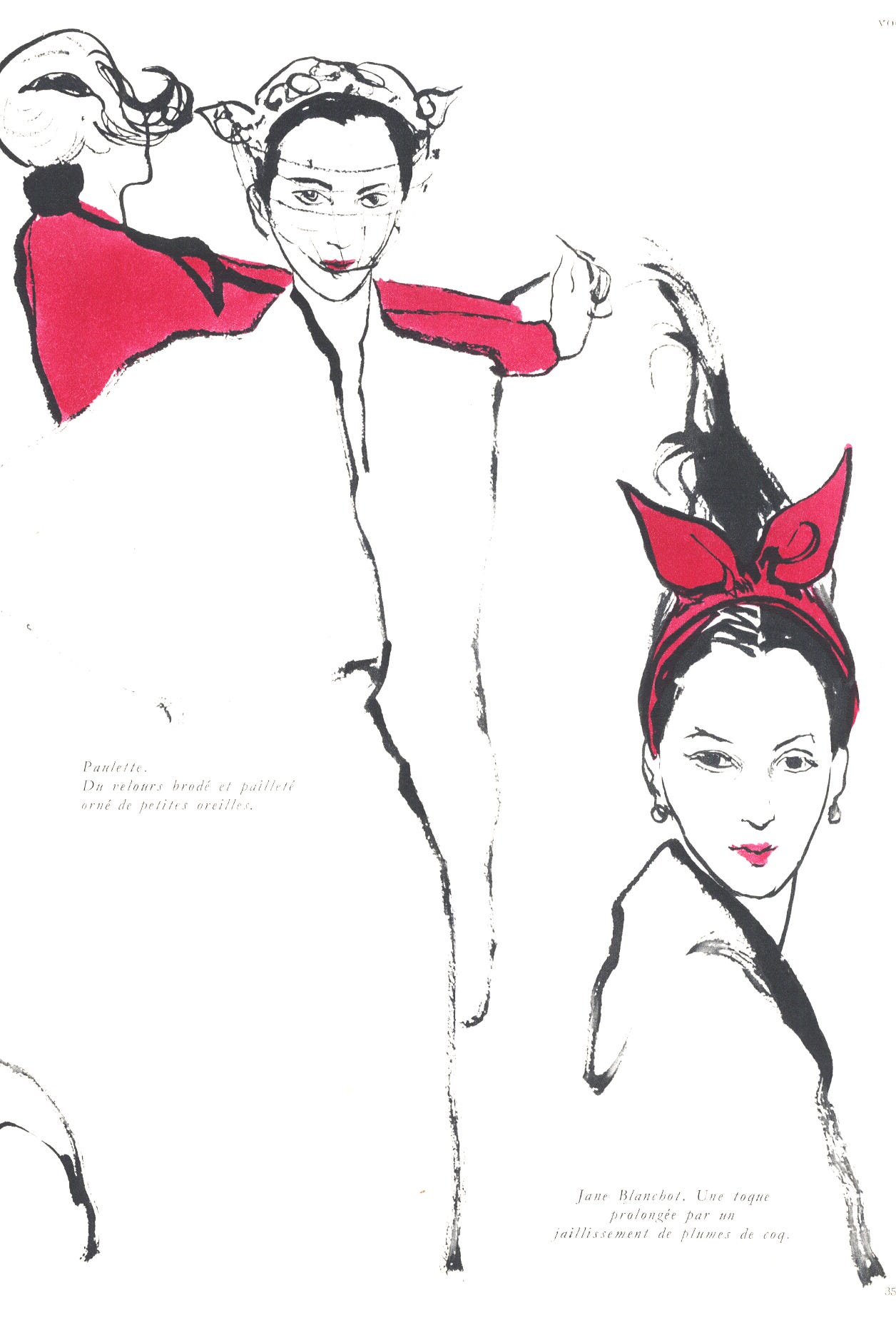

Tom Keogh was an artist of insouciance and snap.His ravishing palette – citrus yellow, moss green, violet, and shocking pink – was counterbalanced by a draughtsman’s natural ease, a flick of the brush forever running dry of black ink. In the late 1940s and early 1950s he drifted through French Vogue, as light as air, as fresh and thrilling as newly squeezed paint. For a time it looked as though he would be a natural successor to Bérard or Vertès but then he appeared to loose momentum and interest. Like Vertès, Keogh was extremely versatile; he painted in oils, illustrated book jackets and short stories, designed for the theatre, movies and ballet, and yet there is a frustrating lack of focus to his career.

He was born in San Francisco in 1922 and studied at the Chouinard Art Institute in California. By the early 40s he had moved to New York and was working as an illustrator and designer for the legendary costumier of the New York City Ballet, Madame Karinska. In 1944 he helped Karinska construct (though not design) the elaborate costumes worn by Marlene Dietrich in Kismet, and in 1948 he would earn his only solo credit as costume designer, for Vincent Minnelli’s musical The Pirate. By then he had entered into a tempestuous marriage with Theodora Roosevelt, the granddaughter of President Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt and, in 1947, the couple moved to Paris.

Keogh was quickly taken up by French Vogue, then under the editorship of Michel de Brunhoff, and his high profile contributions to the magazine triggered a great demand for his work; advertising for Elizabeth Arden and Jean Dessès, Christmas windows at Galeries Lafayette, murals in Arden’s salon des exercises, costumes and sets for the ballet Don Quixote. His private life was no less colourful; though he and Theodora were nominally happy, he began an affair with the fabulously wealthy and eccentric patron Vicomtesse Marie -Laure de Noailles. His wife retaliated by having an affair with the Vicomtesses’ chauffer, complicating an already highly charged situation. There were other affairs and rumours of a suicide attempt and the couple finally divorced, though they remained on good terms. When Theodora began writing a highly regarded, if scandalous, series of novels in 1950 it was Tom who illustrated the covers. Long after their divorce (she would re-marry twice and outlive him by almost 30 years) she would refer to him as “ my estranged but still beloved Tom”

In the early 1950s Keogh stopped working with Vogue and turned his attention once more to ballet, theatre and portraiture. He designed an extended ballet sequence for the Fred Astaire musical Daddy Long legs in 1955, and another for Anything Goes, a Bing Crosby vehicle, the following year. On the latter movie he worked with the choreographer Roland Petit and the dancer Zizi Jeanmaire, and the three teamed up again for Les Belles Damnées at Sadler’s Wells. He illustrated Hemmingway for the Paris Review, and among several book jackets, produced a wonderfully graphic cover for Le Repos du Guerrier. He enlivened his own Dictionnnaire des Femmes with elegantly humorous black and white line drawings in 1963.

Back in New York in the late 1960s after 20 years in Paris, his evocative drawings of the catwalk shows for the first issue of New York magazine in 1968 showed that he had lost none of his panache. Nor did he seem aghast at the modish turn fashion had taken. Eric, Bouché, Bérard and Vertès were all gone, of his peer group only Blossac and Gruau remained and, on the evidence of the New York drawings, Keogh was more at ease than either with the spirit of the time

Tom Keogh died in 1980 aged just 58. His was a strange career, crowded with brilliant achievements and missed opportunities, lacking finally any real cohesion. But for 4 short years, he enlivened Vogue’s pages with a dazzle and verve that have rarely been equalled.

What fabulous style. What a life!

A real pleasure to read 💛