Fellini was entranced: “Her little girl goddess beauty was dazzling. The lunar hue of her skin, the icy blue of her eyes, the golden sparkle of her hair, her exuberance, her joie de vivre, all made her a grandiose, otherworldly figure. I felt she was all aglow,” he said, of his most emblematic star. “It was I who made Fellini famous, not the other way around,” Anita Ekberg snapped to a reporter, years later.

She had a point. Arriving in Rome in 1955 to play Hélène in War And Peace, her first significant role, Ekberg and the Italian capital were instantly simpatico. In less than a decade, Rome had emerged from a period of post war deprivation and division to become the epicentre of international highlife, a byword for pleasure seeking. The ‘City of Sin’, according to Esquire magazine.

The reason, in no small measure, was Hollywood or at any rate Hollywood money. After World War Two, the Italian government passed a law stating that any profits made by foreign movies in Italy must stay in Italy and be spent there. Keen to release funds, expand horizons and to do what television couldn’t, producers began to think of sunny climes and scenic ruins, wide screen and cheap extras, epics and romances. The success of Quo Vadis (1951) and Roman Holiday (1953) bore them out. American stars flooded into the Eternal City. Their days were spent at Cinecittà, the Fascist-era studios built by Mussolini in 1937, their nights at the clubs and cafes and bars along the Via Veneto, where they mingled with princes and playboys, pimps and poets, old money and no money, society high and low.

A plethora of picture-led magazines – Oggi, Tempo and L’Europeo among them – sprung up, eager to record every peccadillo and indiscretion, and a group of ‘action photographers’ – not yet known as Paparazzi – vied with each other for the most explosive and scandalous images. And as those photographers and magazine editors quickly discovered, no one looked better in the flair of a Rolliflex, or embraced the rhythm of balmy nights to rosy dawns with more enthusiasm than Anita Ekberg.

When Ekberg returned to Italy the following year to marry the British actor Antony Steele, crowd control was needed, and by the time she was back at Cinecittà to make Nel Segno di Roma, a sex and sand epic in 1958, she was in the eye of a storm. That summer, she was photographed by Pierluigi Praturlon wading into the Trevi fountain to soothe a cut foot; Tazio Secchiarolli (later dubbed ‘king of the paparazzi’) recorded a 4am fracas in which Steele – by all accounts a belligerent drunk – punched another photographer; and Secchiaroli was also present the night Ekberg danced barefoot, hair flying, straps sliding at the Travastere nightclub, Rugantino. Her unfettered display provoked the Lebanese would be actress Aïché Nana to perform a strip tease to the beat of a tom-tom, which landed her on the front pages and in court.

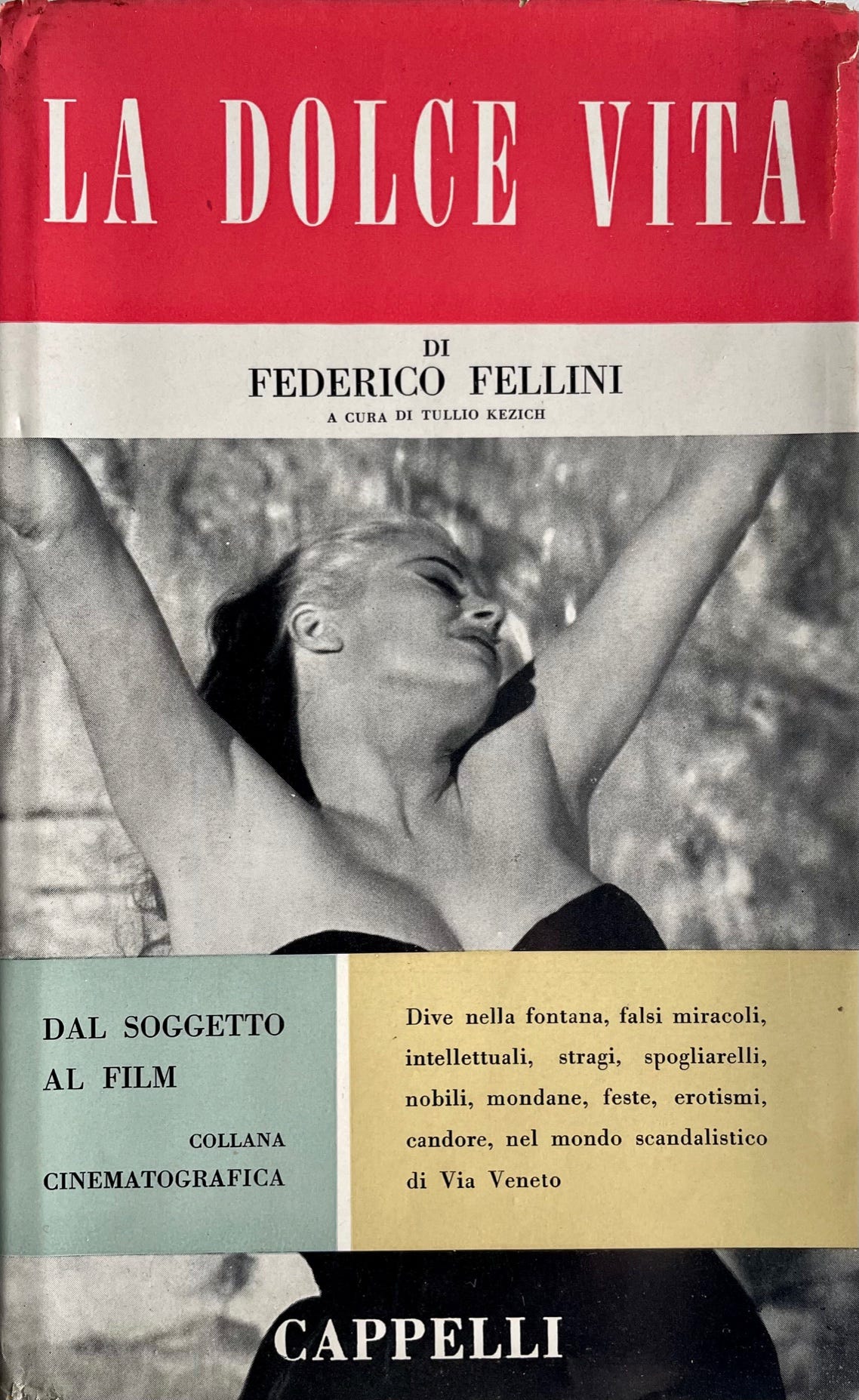

All the while, on the terrace at the Hotel Eden and in in his ‘office’ at the Bar Canova, Fellini was taking note and when he contacted Ekberg with his idea for La Dolce Vita, a fable of a society on the brink of an abyss, her picaresque adventures had been woven into the script. Except, there was no script. Ekberg was nonplussed and anxious that she was being satirised. “Don’t worry,” Fellini told her. “You’re playing Ava Gardner.”

The movie’s most famous scene was shot on a chilly March night. Under a silver gelatin moon, Hollywood star Sylvia Rank (Ekberg) wades into the Trevi fountain. Her evening gown, cut low and hitched high, unfurling in the water like ink. “Marcello, come here!” she calls to Mastroianni, playing a gossip columnist/reporter. She is lost in a dream. He follows, stupefied by her beauty. They don’t quite kiss. The cascade goes silent, dawn breaks and Nino Rota’s haunting score floats into the air. Later, Ekberg enjoyed telling journalists that the water was so cold she lost feeling in her legs and had to be fished out of the fountain, and that Mastroianni wore waders under his suit and got blind drunk on vodka.

She was born in Malmö in 1931, one of seven siblings. As a teenager she modelled and took part in beauty pageants. She was crowned Miss Sweden in 1951 and along with the title came a trip to Atlantic City as a guest of Miss America. Hollywood took notice, but she demurred, turning down Howard Hughes, who wanted to put her under contract at RKO and change her name, her teeth and her nose. She returned home but was back in the US the following year signed to Universal while keeping, she said later, a return ticket to Sweden in her pocket. Her time was spent improving her English and taking dance, deportment and riding lessons. Few people noticed her debut as a ‘maid of honour’ in the western The Mississipi Gambler (1953) other than Tyrone Power, the movie’s leading man, with whom she had an affair. Her role as a ‘Vesuvian guard’ in Abbot and Costello Go To Mars (1953) was hardly more promising and Universal dropped her. She signed a new contract with John Wayne’s production company Batjac, who unaccountably cast her as a Chinese in Blood Alley (1955).

Movies may have found little for her to do, not so the glamour photographers Peter Basch and Andre de Dienes whose rapturous layouts in Life and Esquire highlighted her statuesque Nordic splendour and propelled her to a pin-up stardom. She was known as ‘The Iceberg’ and ‘The Blonde Venus’ and ‘the girl who makes Jane Russell look like a boy.’ The scandal sheets meanwhile kept a bold face tally of her affairs with Gary Cooper, Frank Sinatra and Yul Brynner. In 1955, she received a Golden Globe as ’most promising newcomer’ and by the following year she was famous enough to play herself in the Jerry Lewis/Dean Martin comedy Hollywood or Bust. Pun intended.

La Dolce Vita made Ekberg immortal and perhaps inevitably neither her career nor her personal life could live up to the myth. She was again an arresting presence, playing herself as a giant billboard image come to life, in Fellini’s episode of Boccacio’ 70 (1962) but a return to Hollywood in 4 for Texas the following year was not a success. She moved permanently to Italy, becoming a citizen in 1964. There, she made a string of movies but by the end of the decade her star had waned as the beauty paradigm shifted from eternal female to girl next door, from sex goddess to waif. In 1975, her second marriage to some-time actor Rik Van Nutter ended tumultuously. Ekberg claimed that he had ‘stolen everything,’ emptying her bank accounts and selling her villa and its contents from under her before making off with her Ferrari, her yacht, even a Chinese junk.

She posed magisterially nude for Playboy aged 47 and took the lead in a hilariously lurid ‘giallo’ Killer Nun with Joe Dallesandro in 1978. Thereafter, she semi-retired to her villa at Genzano, outside Rome surrounded by olive trees, guarded by Great Danes. She gained weight – “It’s not fatness, it’s increased womanhood!” she growled to a reporter. Working periodically, she gave lively interviews, her voice a basso drawl, ice clinking in the glass of her favourite local wine. She was supported by an old flame Gianni Agnelli, the only man, according to her friend and confidante Angelo Frontoni, who took nothing from her. In 1987, Fellini and Mastroianni called on her at home for the quasi documentary Intervista, and the two stars watched the shadows of their former selves at the peak of their beauty. Ekberg’s tears did not seem feigned. “There are no women like that in Japan,” a crewmember is heard to say.

Ekberg’s last years proved challenging as ill health and money problems accrued. But she was defiant. “I have no regrets, I’ve lived and laughed and been crazy with happiness,” she said. Fellini once noted that the idea of Anita Ekberg was central to that of La Dolce Vita, and fittingly, when she died in 2015, her image was projected onto the Trevi fountain, the dream still potent.

The Essential Anita Ekberg

War and Peace (1955), director King Vidor

Screaming Mimi (1958), director Gerd Oswald

La Dolce Vita (1960), director Federico Fellini

Boccacio’70 (1962), director Federico Fellini

Killer Nun (1979), director Giulio Berruti

Intervista (1987), director Federico Fellini

Blondes (1999), director Nicola Roberts

Ciao Anita (2019), director Jacques Goyard

The Girl In The Fountain (2021), director Antongiulio Panizzi

Blondes (1999) full length documentary

Genial

Love the new drawing of Anita...