Writer, lecturer and historian Tony Glenville has been attending fashion shows since the early 1960s. We met in Paris 25 years ago and have been friends ever since. When it comes to fashion, Tony knows. I sat down with him to discuss the original 20th century style bible, La Gazette du Bon Ton.

DD: When did you first encounter La Gazette du Bon Ton?

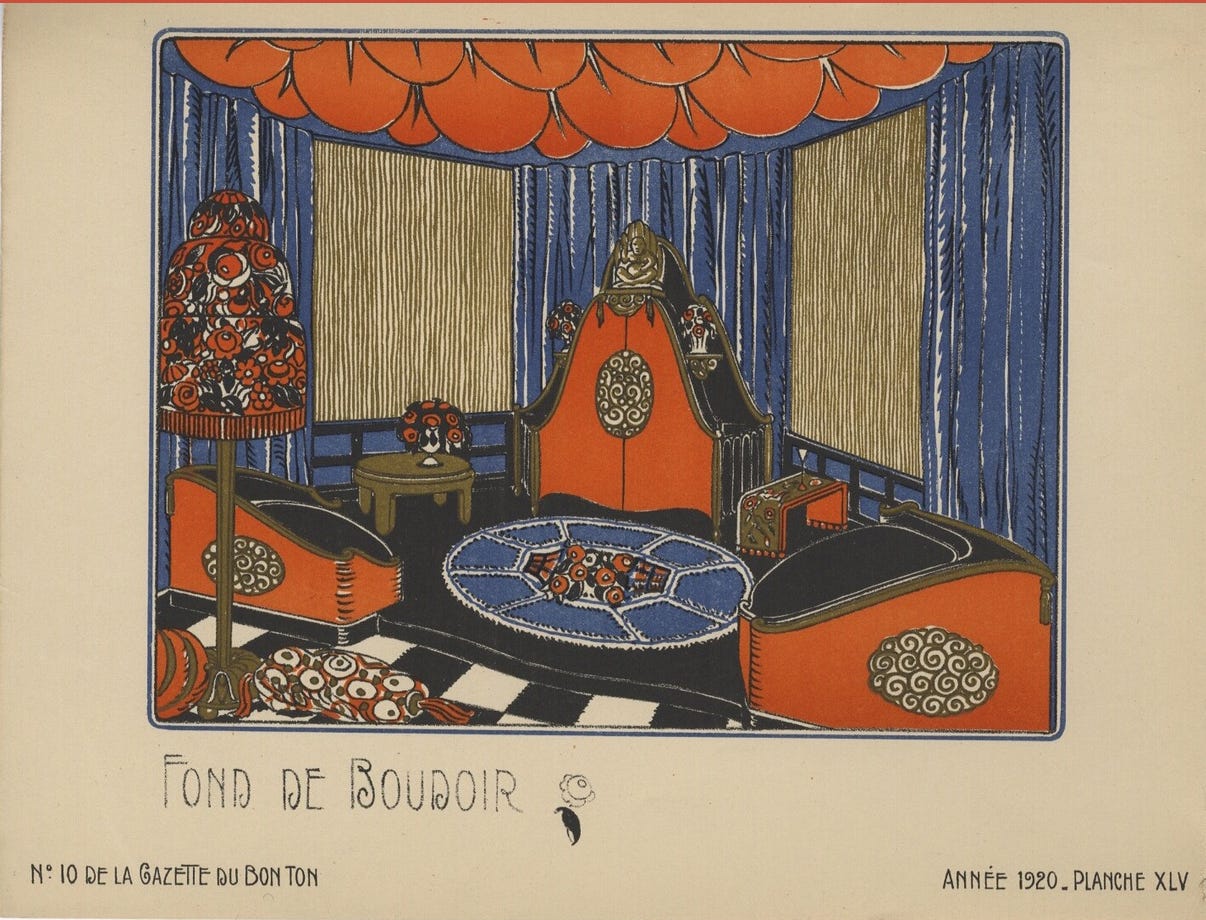

TG: In 1964. I was a 17-year old fashion student and had gone to the library at the V&A to look at their bound volumes of the magazine. I knew this was a primary source but other than the pochoir plates, knew little of what I was going to find. I was researching Paul Poiret, who was pretty much a forgotten figure at that time. It was a dull November afternoon but the illustrations leapt into life as I turned the pages. The colours were as fresh, vibrant and opulent as the day they been created.

DD: The start of an affair!

TG: Certainly an affair, but also a bit of an obsession.

DD: It was first published in November 1912, an extraordinary period in history.

TG: It appeared with impeccable timing, just as the new century gathered pace and the world shifted its view of what constituted taste in fashion. An entirely new outlook on style was to shape the period, either side of the First World War. There was the opulence of the Ballets Russes, and their experimentation with new composers and artists. Then, the shift from waltz to tango to jazz. There was the early cinema and the development of cars and planes, speeding up communication and travel. It was an exciting shift, visually, from the Edwardian era to the Roaring Twenties.

DD: Paul Poiret may have been largely forgotten by the 1960s, but at that time he was a highly influential figure, known as the Pasha of Paris, or Le Magnifique…

TG: He was hugely important. In many ways, Poiret created the template for the couturier of today, not only with his designs for clothing, which were revolutionary, but with his restaurants, fragrances, window displays and so on. Like many of today's designers he also entertained lavishly and had a tremendous flair for publicity.

DD: I enjoyed reading about his ‘Thousand and Second Night’ party, with its roaming peacocks and ibis and harem girls. Extravagance almost unimaginable today. How involved was he with the launch of La Gazette?

TG: More indirectly than directly. In1900, he created a deluxe limited-edition portfolio of his key looks, illustrated by Paul Iribe. It was called Les Robes de Paul Poiret and had an extraordinary modern graphic quality. This was followed in 1911 by Les Choses de Paul Poiret, which was illustrated by Georges Lepape. The success of the albums certainly inspired La Gazette’s publisher Lucian Vogel.

DD: Vogel was an art director, publisher and man about town

TG: Yes, and he was married to Cosette de Brunhoff, the sister of Michel de Brunhoff, later Editor of Vogue Paris. Between them, the two men ruled creative publishing in France for several decades with titles such as Comedia Illustré, Vogue, Vu, and Le Jardin des Modes. Cosette became the first rédactrice en chef (editor-in-chief) of Vogue.

DD: I loved Cocteau’s comment that Iribe’s drawings ‘disgust mothers’. Modern fashion illustration, by which I mean artists being encouraged to interpret fashion, as opposed to simply recording it, really began, or at least came of age, with Poiret and these albums.

TG: I agree. Portrayal of clothing rather than ‘fashion’ goes back to the Romans and the Egyptians of course, but the idea of drawing fashionable clothes really starts with Wenceslas Hollar in the 17th century. Fashion illustration proper is tied directly to the increased availability of printing and the creation of the magazine in the late eighteenth century. The most stunning example of this was Gallery of Fashion, published by Nicolas de Heideloff, which ran from 1794 to 1804 and contained fashion plates with extraordinary details such as hand applied metallic paint. Then there were the much-collected Regency plates of the Empire and Jane Austen period, which is also when fashion cartoons hit their stride with Gillray and others lampooning fashion, a habit that continues today. Through the nineteenth century, artists such as Vernet, Toudouze and Sandoz continued the tradition of superb draughtsmanship, though they are rarely celebrated now.

DD: Their work is brilliantly skilful, but the drawings were principally about imparting information, telling you everything you needed to know about the ribbon and the trim but conveying little emotion, at least to my eyes.

TG: True. The plates generally feature a single figure or a pair of figures. Backgrounds and atmosphere are almost non-existent.

DD: The Poiret albums functioned primarily as advertising for the designer and what we would now call his ‘brand’ but La Gazette was very much a magazine.

TG: Its stated areas of interest were ‘Arts, Modes and Frivolities’ and I think it was conceived as much for the satisfaction of the contributors, all of whom seemed to know each other or have family collections, as it was for its readers. It was the epitome of what we now refer to as ‘vanity publishing.’ And it didn't just focus on women's fashion. La Gazette included pieces on menswear, childrenswear, admittedly usually by Madame Lanvin, heraldry, interiors, floral arrangements, theatre, cars and carriages. It had a limited print run of 2,000 issues, sold both at kiosks and in the salons of the couturiers, giving it a cachet, and an appeal to the elite.

DD: Let’s talk about the artists the magazine employed. They were a wonderfully eclectic group, most of whom had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and were known as ‘The Beau Brummel’s of the Brush’ and ‘The Knights of the Bracelet’.

TG: Vogel appeared to impose few restrictions on them, rather in the way that Diaghilev encouraged his collaborators to ‘astonish me’. The core group included Georges Lepape, George Barbier, André Marty and Pierre Brissaud. But Erté, Leon Bakst and even Raoul Dufy also contributed. The magazine encompassed the graphic perfection of Bernard Boutet de Monvel and Eduardo Benito and the modern art freedom of Thayaht, while Étienne Drian’s deftness of line paved the way for Eric (Carl Erickson) and René Bouché.

DD: Vogel was certainly a canny businessman. He had the magazine sponsored by a group of leading couturiers – Cheruit, Doeuillet, Doucet, Paquin, Poiret, Redfern and Worth – in exchange for featuring their designs in each issue. An early kind of advertorial.

TG: Poiret was the first on board and at that point his name carried enough weight so that others followed. It was Vogel’s idea to allow the artists to draw both real fashions, and their own imaginative creations.

DD: La Gazette was certainly lavish and beautifully realised. A new typeface, Cochin (designed by Georges Peignot) was utilised and its attitudes and aims were, as you say, the last word in elitism. A yearly subscription in 1912 cost almost the equivalent of an average monthly wage.

TG: It was the loose-leaf Pochoir plates, with their witty or elliptical captions, that made it so covetable. The numbers of plates varied but there were usually around ten in each issue, created using a series of stencils (Pochoir literally means stencil). As many as 80 might be used on a complex illustration, with each colour – usually gouache – being laid over the next, resulting in intense opaque tones. It was an extremely expensive and labour-intensive process that eventually gave way to lithography.

DD: I read that in the early part of the twentieth century there were hundreds of workshops dedicated to the making of Pochoir prints in Paris, and that La Gazette’s artists had final approval of the plates and only signed them when they were happy.

TG: As a group, the artists were greatly respected by the editors. They had freedom, as did the writers.

DD: I recently saw a complete run for sale online for $33,000.

TG: I would say that even library copies cannot be relied on to be ‘complete’. Anyone buying expensive volumes or runs would do well to thoroughly investigate the contents, page by page. Since the issues are loose leaves, the contents, including the advertisements and the number of plates, are all variable to a degree. Many plates have been sold, framed and distributed away from the complete issues.

DD: After a break during the First World War, La Gazette was re-launched in 1920, but Vogel sold it the following year and eventually joined French Vogue as art director. The last issue appeared almost a century ago, in 1925, and yet it continues to entice an extraordinary fascination.

TG: It was a stylish publication aimed at a stylish market and above all it was a showcase for illustrators. It offered them an opportunity to flex their illustrative muscles and convey the drama of the fashions and women’s’ posture and behaviour as no photograph ever could. It's interesting that many of the designers of the time such as Beer or Redfern are now remembered almost solely through these illustrations.

DD: In the years since there have been a number of publications that owe a debt to La Gazette du Bon Ton.

TG: Visionnaire, Egoïste and Acne Paper spring to mind in terms of creativity and limited editions. La Mode en Peinture was also a great example, as was a brief flurry of Vanity edited Anna Piaggi, featuring the work of Antonio Lopez. But La Gazette remains the original and in many ways the best. To me, and to many collectors, it’s unique.

DD: I know you have been avidly collecting the Pochoir plates over the years. If I forced you to choose just one, which would it be?

TG: I’m avidly collecting the issues! It’s so great to place the plates in their original context. I guess it’s a Poiret, and probably one of those I first saw back in 1964, ‘Dieu Qu’ille Fait Froid’. And, if I forced you to choose?

DD: It has to be a Drian. I would probably pick ‘Avenue du Bois’. Drian was a remarkable artist. He wasn’t an overt stylist, like of many of his peers. He drew what he saw. And yet there is a stunning graphic quality there that foreshadows Gruau, who incidentally, revered him.

All images courtesy of the Tony Glenville archive

Tony Glenville’s La Gazette reading list:

Anon. 1979 French Fashion Plates in Full Colour from the Gazette du Bon Ton ( 1912-1925), America: Dover Publications

BA Holley R. & Bordet D. & Lelieur A.M. 1982 Paul Iribe, France : Denoel

Bleckwenn R. 1980 Gazette du Bon Ton - Eerste Jaargang 1912/1913 Holland: Bibliophilia

Calahan A. & Zachary C. 2015 Fashion & the Porchoir - The Golden Age of Illustration in Paris, United Kingdom: Thames & Hudson

Lepape C & Defert Thierry 1983 George Lepape ou L’Elegance Illustre, France: Herschel

Kerr G. 2012 Art Deco Fashion Masterpieces, United Kingdom: Flame Tree Publishing

Ridley P. 1979 Fashion Illustration, United Kingdom:Academy Editions

Robinson J. 1976 The Golden Age of Style - Art Deco Fashion Illustration, United Kingdom: Orbis Publishing Ltd

Thornton N. 1979 Poiret, United Kingdom: Academy Editions

Weill A. 2000 Parisian Fashion - La Gazette du Bon Ton 1912-1925, France: Bibliotheque de l’image

Two geniuses of fashion illustration!! Unbeatable and very interesting document. Thank you David