Giovanni Boldini’s bravura technique, dazzling sense of style and unapologetic appreciation of women and the beau monde defined him as the supreme social portraitist of his day, the Warhol of the Gilded Age.

Throughout his long career, Boldini painted landscapes, seascapes and genre scenes. He made highly acclaimed portraits of his fellow artists (Degas and Lautrec among them) but his real subject, and abiding interest, was women, specifically,Women of Fashion.

Lacking the restraint (and at times it must be said, the sensitivity), of his peers, Sargent, Helleu and Whistler, his portraits, are startlingly sensuous and direct; eyes shine, bosoms heave and straps slide from powdered shoulders. But there is no time for indolence, Boldini keeps his subjects in perpetual motion as they spin through the picture plane or perch on a strategically placed chaise before rushing off to some assignation or other (a ride in the Bois perhaps, or supper at Maxim’s? )the artist had a particular gift for suggesting not only the gaiety of the moment, but the narrative beyond the canvas.

His virtuoso portraits from the 1890s up to the outbreak of the World War1, with their swooping rococo brushstrokes, attenuated proportions (look for example at the length from hip bone to knee of Mme Charles Max) and lush rendering of haute couture gained him an international following and would have a lasting influence on the pioneers of Grand Manner fashion illustration in the first half of the 20th century; Drian, Gruau, Bouché and Eric.

He was born Giovanni Giusto Fillipo Maria Boldini in Ferrara, Italy, on December 31st 1842, one of 13 children. Showing early artistic promise he trained initially with his father, a painter and picture restorer, and later, after his lack of height ruled him out of military service (he was a centimetre too short), he enrolled in L’ Academia di Belle Arti in Florence in 1862. There he fell in with the Macchiaoli a loosely knit group dedicated to shaking up the Academia’s traditions by espousing the virtues of directness and spontaneity that would become hallmarks of his work.

Boldini’s social antennae were already finely tuned. He found early patrons among the wealthy British expatriates living in Tuscany. He painted a series of murals depicting rustic scenes for La Falconiera the country villa of Sir Walter Falconer, and picked up useful and socially prominent portrait commissions in London, following introductions from Sir William-Cornwallis West. By 1871, he had established himself in Paris and was living in the Place Pigalle with his model and lover, Berthe.His prolific output of lively, small-scale street scenes and genre pieces quickly found favour with the public and, just as importantly, attracted the attention of the eminent dealer Adolphe Groupil, with whom he signed an exclusive contract that would run until 1888.

His debut at the Salon de Mars in1874 consolidated his success, enabling the upwardly mobile artist and his ’fiancé’ to take a house at Versailles. Boldini enjoyed his early popularity. He travelled widely and exhibited in Berlin, London and in Florence.

His ebullient Pariginisimo personality and prodigious talent led him to forge friendships with the artists Degas, Whistler, Lautrec and Sargent, all of whom he would paint during this period

In May 1884 Sargent unveiled his Portrait of Madame **** (which became known as Portrait of Madame X). His depiction of the American born Virginie Gautreau with her plunging décolleté and coolly detached sexuality outraged the public, the critics and, most vociferously, the sitter’s mother ”My daughter is ruined! ... She’ll die of chagrin!” she wailed as she tried to get the painting removed from public view. The criticism rumbled on and later that summer Sargent left Paris for London, where he re-established his reputation and in 1886 Boldini took over the lease on his former studio and apartments at 41 Boulevard Berthier.

In 1888 Boldini’s portrait of Emiliana Concha de Ossa, the daughter of a Chilean diplomat, marked a turning point. Scaled to match Sargent’s heroic proportions and owing more than a passing debt to his friend Degas, the portrait also sowed the seeds for Boldini’s mature style. In it, he matches a flattering likeness with a full-blown sense of style while reducing the background to a vague theatrical scrim that serves only to further flatter his subject. Winning the Gold Medal at the Exposition Universal in 1889, Boldini announced “I loved the portrait too much, I’ve kept it for myself.” Later he quietly made a copy for Mlle Concha de Ossa.

The relationship between artist, sitter and public had been slowly evolving during the last quarter of the 20th century. Portraiture, once the preserve of the aristocracy, was increasingly seen as a form of social advancement by the nouveau riche and as the scandal over Madame X gradually subsided, it was clear that demi-monde would no longer be excluded from the Salon. Not every one was happy about the shifting social mores:“Women used to have themselves painted for their husbands, their children…portraits used to show discreet, reserved poses…now they have been turned into noisy advertisements,” noted one commentator wearily.

By the 1890’s Boldini had entered his Grand Period and throughout the decade and beyond a Proustian cast of actresses and heiresses, entrepreneurs and aesthetes whirled through the Boulevard Berthier studio, eager to make just such advertisements of themselves..

Fashion and display had always played a pivotal role in social portraiture, but during the Belle Époque it assumed an even greater significance as couturiers such as Worth provided clothes directly to the artists for portrait sittings (an early manifestation of the 21st century phenomenon in which designers scrabble to get their clothes onto the ‘right’ celebrity for public appearances). Cecil Beaton, not an admirer of Boldini’s, pinpointed one reason for his popularity:”Boldini had an awareness of fashion far more acute than that of Sargent…instead of painting his subjects in the somewhat nebulous draperies that the American painter thought would not ‘date’… Boldini was able to create on his lightening struck canvases an apotheosis of all that the Rue de la Paix and the Place Vendôme could offer.”

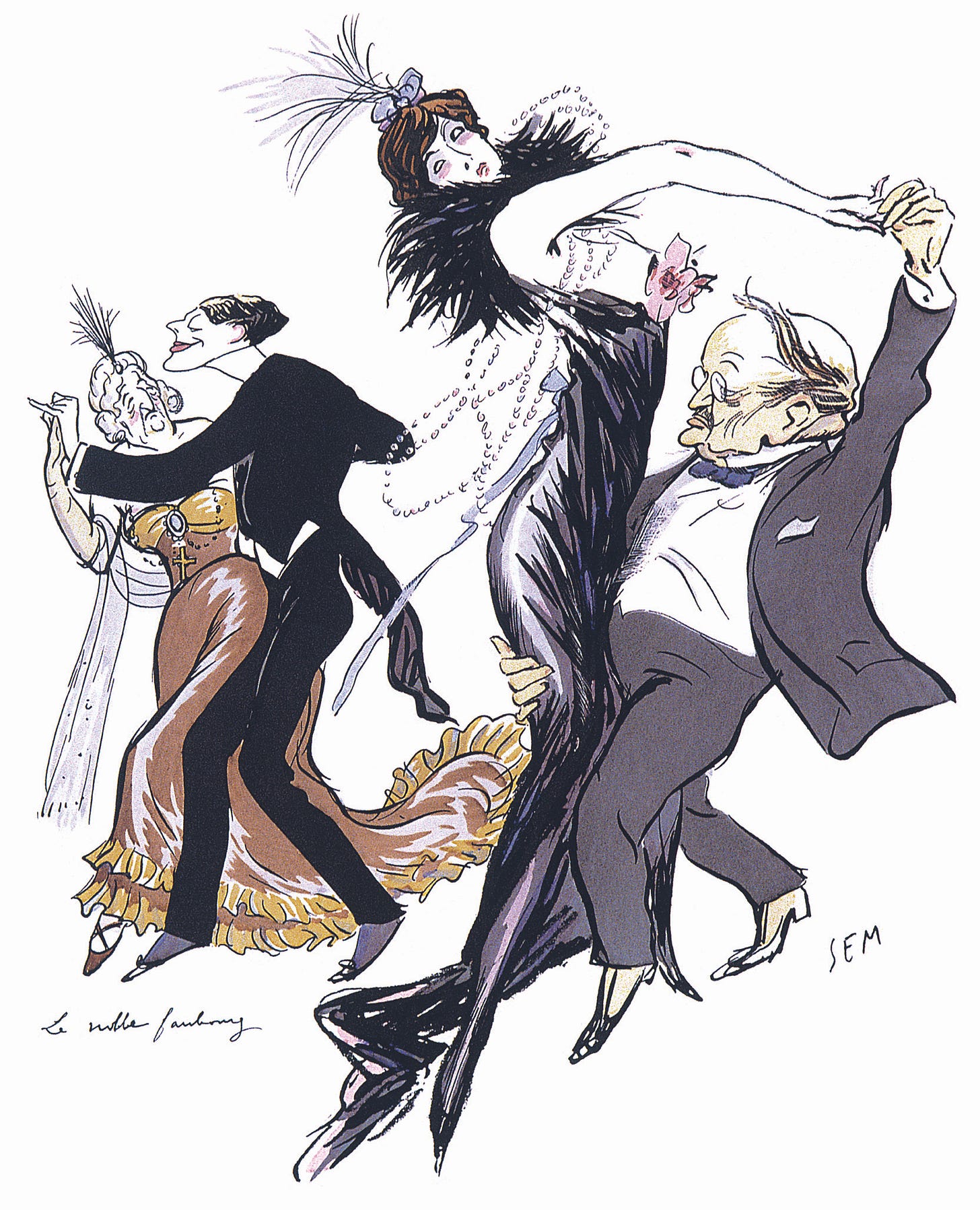

Commentators were divided “He is the magician of movement,” sighed the choreographer Serge Lifar. “The non pareil parent of the wriggle and chiffon school of portraiture,“ sniffed Sickert. “The artist of his Age,“ declared the caricaturist Sem. It is unclear what he made of the seismic shifts in the art world during the opening years of the 20th century, what his reaction was to the appearance of the Fauves in 1905 or to Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907, and while some would later claim that Boldini’s frenetic energy marked him out as a Futurist, he declared no such allegiance, and he would certainly have deplored the outright misogyny of their early manifestos.

He spent the war years in Nice and in London and received the Legion D’honneur in 1919. In 1929, aged 86, he married Emilia Cordona, a journalist decades his junior. “I never meant to get so old, he told the wedding party “it happened all at once.”

He continued to make portraits but the florid pictorial style that was once a barometer of the times was increasingly at odds with the Art Deco period and he concentrated instead on painting nudes, investing them with predictable kinetic energy.

Boldini died in 1931, and reviewing an exhibition at the Wildenstein Gallery, in 1933 Time Magazine summed up the prevailing mood; “He was the painter of the pompadour, the champagne supper and the ribbon-trimmed chemise” it noted, “The passing of the petticoat was the passing of his art”

Boldini’s reputation has fluctuated in the intervening years. Though his work fetches high prices at auction and can be found in most of the major museum collections, critics - outside Italy where he is revered - tend to dismiss him as a sybaritic first cousin to Whistler and Sargent and until recently there was no biography, monograph or catalogue raisoné available in English.

But, for almost two decades he reflected the glimmer of the Golden Age, and how poignant they look now, Les Femmes Boldini, caught in his beautifying gaze as the world rushed towards modernity.

Thanks David!! Adore Boldini.

Lovely works. He certainly had an innate ability to paint fabric and cloth. Thanks for the story David.